Camera Obscura

It’s a simple enough demonstration of the nature of light: cover the windows to make a room (Latin: camera) completely dark (Latin: obscura), then make a small hole facing the bright outdoors. When your eyes adjust, you will see the outside world projected opposite the pinhole, upside-down and backwards, but in full color and moving in real-time. It’s still a beautiful sight today, but don’t look for photos online; do it for yourself.

The history of optical science begins with the camera obscura. Euclid and Aristotle in Greece (4th century BCE), Mozi in China (4th century BCE), Al-Kindi and Ibn al-Haytham 9th-10th century AD) all described the pinhole effect and laid foundations for future theories of optics and light.

As a drawing machine, the camera obscura has some advantages. Well, actually, one advantage: this is a perfect representation of real life flattened on a wall for tracing. This is a projection long before anyone had projectors; even before lenses were invented. But as a drawing tool, there are some disadvantages. First, the room is pitch black, and the projection is quite faint. A larger hole makes for a brighter but fuzzier image, so the artist must trade clarity for fidelity. The image is upside-down and backwards, which is not a deal-breaker, but it is awkward. And then there is the projection itself. To trace the projection, your hand and stylus will block the projection while trying to draw it. Frustrating.

So beginning in the 1600s, artists and inventors modified the operation to be more conducive to drawing. Athanasius Kircher solves some of the problems in 1646: he adds a screened room inside the darkened room, so the artist can draw the rear projection. The image is still upside-down but correct left-to-right, and now the artist is not blocking the projection. By this time, lens manufacturing has also advanced enough to provide shape focus and bright images.

Further improvements remove the room entirely. By having a small portable box and a shaded ground-glass screen, artists can trace the image on the rear-projected glass through thin onion-skin or trace paper. Portable boxes and tents, with lenses and mirrors to double-reverse the image to correct orientation were popular tools by the 19th century, until photography usurped the need for the camera obscura. But then again, the first photographic cameras were the same form factor as the box camera obscura, so I guess the camera obscura never totally went away.

Click here to browse by this category.

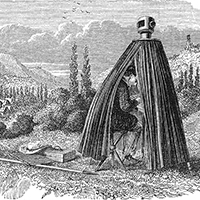

Camera Obscura Tent

Queen and Company

1880

Camera Obscura

Edmund Atkinson

1875

Camera Obscura

Edmund Atkinson

1875

Camera Obscura Tent

Edmund Atkinson

1875

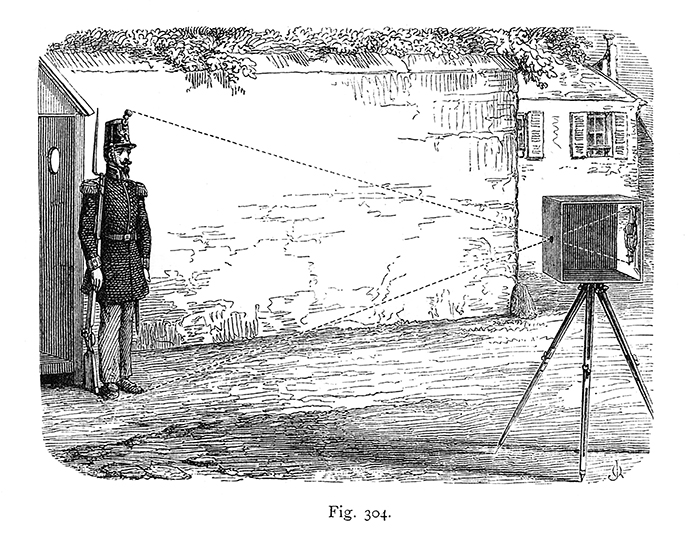

Chambre Noire (Camera Obscura)

Alphonse De Neuville

1867

Camera Obscura

Adolphe Ganot

1864

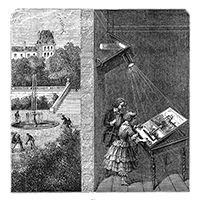

Camera Obscura and Camera Lucida

James W. Queen

1859

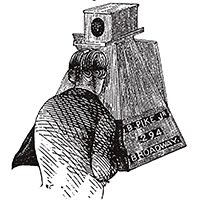

Draughtsman's Camera Obscura

Benjamin Pike, Jr.

1856

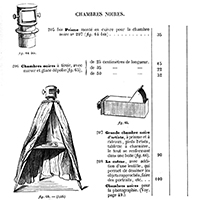

Camera Obscuras (Chambres Noire)

Lerebours et Secretan

1853

The English Painter

Carl Jakob Lindström

1830

Click here to view more machines in this category.